Indoor cycling academy

Recovery at work

What is Training Stress Score?

Training Stress Score (TSS) is something I invented in 2002 in collaboration with Dr Andrew Coggan. It’s a composite number that takes into account the duration and intensity of a workout to arrive at a single estimate of the overall training load and physiological stress created by that training session.

Put another way, it quantifies the training stress on your body after a workout and is applicable to power-based cycling or rowing. [For a briefing on power training, see RIDE HIGH issue 16.]

“TSS lets you track the cumulative stress of each workout on your body to ensure you’re resting enough”

It was a measure I knew I needed to help my athletes accurately understand how hard each workout was compared to others. I also knew I could use this data to shape a plan to peak them at exactly the right moment for big events. Dr Coggan provided the science!

Why is it important?

Before we invented TSS, kilojoules (kJ) – how much energy you burned – were used to quantify the stress of a ride. The problem with this was, it didn’t acknowledge ride intensity: you can ride for longer at a lower intensity and burn the same kJ, but the physiological stress on your body will be nowhere near the same.

TSS gives a far more accurate picture of how much stress you can create. Most important of all, it lets you cumulatively track this stress, allowing you to build a picture of your chronic training load (the cumulation of everything you did between 15 days and six weeks ago, and with it your overall fitness) and acute training load (your workouts over the last two weeks, and with it your current fatigue) to understand the Training Stress Balance in your body today.

This information, in particular the chronic training load, tells you exactly when you should push hard in training and when you should rest. It allows you to continually strike a good balance between fitness (which results from training stress) and freshness (which results from rest) to keep improving – and, where relevant, to hit top form for your event.

As an indoor cycling instructor, it allows you to track the cumulative stress of each workout on your body to ensure you’re resting enough – most injuries are down to insufficient recovery – without losing fitness.

How do you calculate TSS?

As I say, TSS takes into account both workout duration and intensity, with intensity based on the individual’s FTP (functional threshold power).

The easiest way to understand TSS is that you score 100 points if you go as hard as you can – that is, if you cycle at your personal FTP – for an hour. From that benchmark, it’s easy to relate it to other workouts.

“After six weeks of instructing two cycling classes a day, your chronic training load could be 160: the same as a pro at the end of the Tour de France!”

Basing it on FTP makes it scaleable, too: Bradley Wiggins cycles at his super-high FTP for an hour and gets a score of 100. A deconditioned individual cycles at their 80-watt FTP for an hour and gets a score of 100. All you need is an accurate personal FTP.

Some software – such as TrainingPeaks, which you can download as an app – works out the TSS of each ride for you, and there are a few bikes that include this score on their console. If you don’t have access to that, though, it isn’t too hard to calculate the TSS of a ride yourself.

The equation is TSS = {[(duration (s) x normalized power (W)) x IF]/(threshold power x 3600 s)} x100 – but don’t be put off by how it looks, as it isn’t actually that complicated!

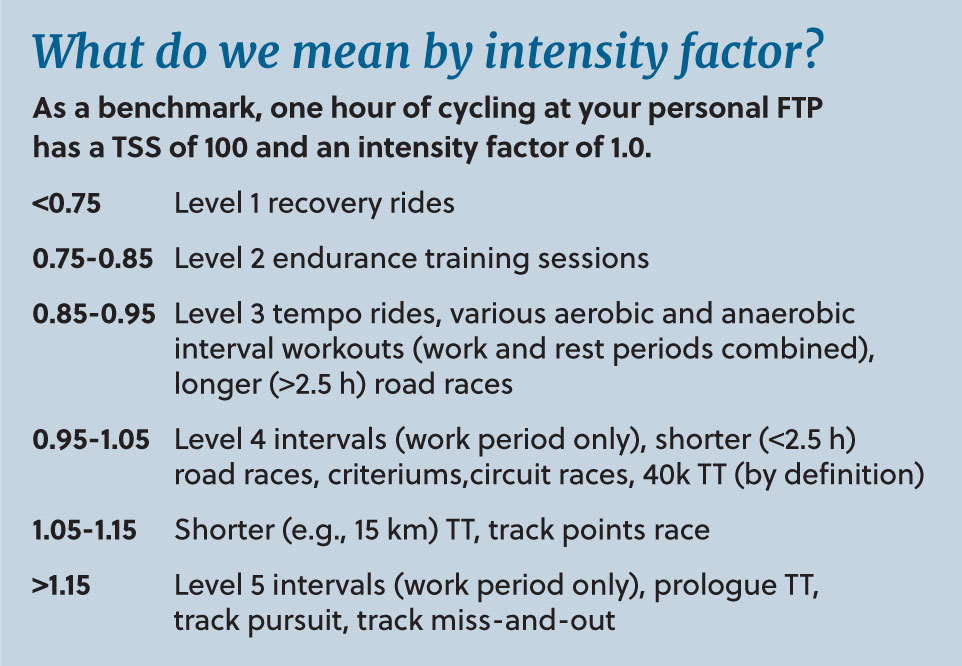

First, take the workout duration in seconds and multiply that by normalised power (which in the context of studio cycling is almost always average wattage), then multiply all that by the intensity factor (see end of this article: What do we mean by intensity factor?) This is the only bit of guesstimating you’ll need to do, as this figure won’t be in your bike. However, you can get a pretty good idea of the intensity factor simply by dividing your average power (wattage) throughout the class by your personal functional threshold power.

“As a basic guideline, I’d advise that if your chronic training load hits 115, you need to rest. That could just mean taking it easy in class.”

You then divide this figure by your personal FTP x 3600 (seconds, to get it up to an hour). Finally, multiply all that by 100 – just because we wanted to present scores as full numbers!

What does TSS mean in practice?

If your score is less than 150, we categorise that as low stress – that is, it should be relatively easy to recover from that workout by the following day. Note that recovery is not the same as being totally fresh: you may still have sore muscles. However, it’s likely you could produce the same effort again the next day, or at least get very close to it. This is how we define recovery.

A score of 150–300 is medium stress: you should have recovered by the second day. High stress is TSS 300–450, where residual fatigue is likely to be around for a few days at least. And then epic is a TSS of more than 450, and here you’re looking at anything from a few days to a few weeks before you can get on the bike and do the same again. The muscular soreness might be gone, but your cardiovascular system still needs more time to recover.

You talk about cumulative load…

Yes, and this is where TSS becomes really valuable. Let’s move away from elite road racing examples and focus purely on indoor cycling instructors to bring this to life.

Every single ride has its own TSS; a typical hour-long indoor cycling class – with its sprints and climbs but also its recovery sections – will have a score of around 65–90. So, let’s say TSS 80 as a rough average.

Now let’s assume an indoor cycling instructor teaches a class a day. Six weeks later, their chronic training load is 80. That’s do-able. Even TSS 100 a day is do-able. Your body adapts to training stress after all – it’s how we get fitter – and a load of 80–100 is a moderate yet solid level of stress.

But what if they’re instructing two cycling classes a day – not uncommon – and they’re cycling them ‘properly’, by which I mean they’re in the saddle hitting all the %FTPs they’re telling the class to hit. Do that every day for six weeks and all of a sudden, chronic training load is 160 (plus any other workouts they happen to be doing).

Now let’s consider that cycling pros, when they reach the end of the Tour de France, have a chronic training load of 160–180 – and then they rest!

Now we can begin to understand why indoor cycling instructors get injured or sick when they’re doing too many classes, and why it doesn’t actually take much for class load to tip over into being too much.

So, when does an instructor need to rest?

First things first, as an instructor, you should absolutely be logging the TSS of every class you instruct, so you build up an accurate picture of your chronic training load (CTL). You then listen to your body and identify what your CTL is when you feel you can’t perform any more. As soon as you see yourself approaching this number in the future, you know you need to start thinking about building in some rest.

“Remember it’s about chronic training load: one day off doesn’t immediately undo the last six weeks of effort”

As a basic guideline, I’d advise that if your chronic training load hits 115 – if you add up the TSS of all your rides over the last six weeks, divide by 42 to get an average daily score, and that average is 115 or more – you need to rest.

(Note: Specialist software will weight more recent workouts higher than workouts six weeks ago. However, for the purposes of simplicity, calculating an average daily TSS as above will suffice.)

Rest could mean taking it easy in class, whether that’s ‘faking it’ rather than actually cranking it up in the saddle, or getting off the bike and walking the studio floor to offer encouragement and motivation.

It could mean taking a break altogether, if schedules allow. But even here, remember that it’s about chronic training load: one day off doesn’t immediately undo the last six weeks of effort.

Read more: Hunter’s previous RIDE HIGH article – on why he believes indoor cycling classes should always be based on power – can be found here.

Read more: Hunter’s previous RIDE HIGH article – on why he believes indoor cycling classes should always be based on power – can be found here.

Conceived, powered and funded by BODY BIKE®, RIDE HIGH has a simple mission: to celebrate and champion the very best of indoor cycling, sharing ideas, stories and experiences from around the world to inspire the sector on to even bigger and better things. Subscribe for free by leaving your details below and we'll send indoor cycling's hottest news direct to your inbox three times a year.